Limitations

- Introduction

- Avoiding the Obvious

- Insoluble Problems, Soluble Opportunities

- Bottomless Wells?

- Oil, Peaking?

Values

- Introduction

- Trouble with Ideology

- The Good Life

- Changing Separately and Together

- Eating for the Planet

- Small Steps, Large Ideals

- Offsetting Without Tears

Design

- Introduction

- Dead Spaces

- Requiem for the Car Industry

- Smart Cars, Hybrids, and Our Spaceship

- Hip Deep in the Big Muddy

- The Virtues of Age

- Two Suburbs—An American Journey

- The Wasteland at the End of the Street

Strategy

![]()

Dead Spaces

Development and Death • Design for Hope • Principles of Land Use Planning

Part 1—Development and Death

Few places in this world are more sad than a derelict shopping mall. Built to face inward, its outer walls are dead space, often with no windows. Acres of empty parking lot surround it. On a windy day, old paper—flyers advertising sales in the stores, chewing gum wrappers, torn up shopping bags—whirl and flutter like the ghosts of some nightmare past. The doors are locked, usually chained, and any windows that were in the outer walls are boarded up and blank. One or two signs, sometimes with letters missing, mark the now-departed stores that were there. And all is silence.

Few places in this world are more sad than a derelict shopping mall. Built to face inward, its outer walls are dead space, often with no windows. Acres of empty parking lot surround it. On a windy day, old paper—flyers advertising sales in the stores, chewing gum wrappers, torn up shopping bags—whirl and flutter like the ghosts of some nightmare past. The doors are locked, usually chained, and any windows that were in the outer walls are boarded up and blank. One or two signs, sometimes with letters missing, mark the now-departed stores that were there. And all is silence.

More and more, in many places in the United States, we are seeing these dead hulks, as developers buy up green land, pave it, build a new mall, and then move on when business disappears or when the next mall down the road attracts all of the old mall's customers. The results are ugly and disheartening, and their larger implications hardly bear thinking about.

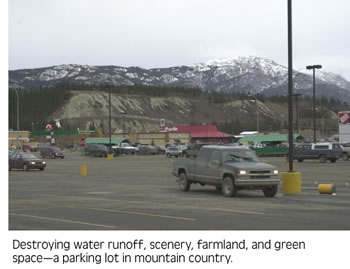

Each mall includes the inevitable parking lot, so enormous that finding one's car after shopping is often a major undertaking that wastes half an hour or more. Each parking lot, in its turn, replaced acres of grass, trees, or farmland. Even when it was successful, the mall contributed to problems with water runoff and pollution. Once it has become derelict, it still does—and it is often unclear who, if anyone, is responsible for cleaning up the mess and repairing the damage. Worse, the odds are that the mall has become derelict because another and almost certainly larger mall has superseded it. Thus to the problems created by the mall that is now derelict, we have added the problems created by the new mall that is (for the moment) successful. Both are, in ecological terms, dead space that is helping to destroy our planet.

The results of this kind of development can be dramatic. Forty years ago, Bucks County, just outside of Philadelphia, was the central character in a bucolic diary, Area Code 215: A Private Line in Bucks County, by Walter Teller. The book is a kind of modern Walden, with reflections on nature, farming, gardening, canals, and the neighbors. It is a comforting book to read. People go about their business; each day brings rain, sun, snow, clouds, and all shades of weather. There is no flooding or natural disaster in this book because in those days Bucks County was a kind and gentle environment.

The Bucks County that Teller describes has been gone for at least twenty years, victim of tract house development and mall-style retailing. Much of the farmland is gone and paved over. There are few derelict shopping malls, because Bucks County is prosperous. But there is plenty of dead space—and with it, flooding and natural disasters where before there were none. Some riverside communities now flood annually, although each year the residents hope that this flood will be the last.

It will not. There is too much paving and too little soil to absorb the rain. And in the long run, the busy malls that are the source of most of the problem may become less busy and be succeeded by bigger, gaudier ones. It is a cycle which, if we do not find a way to stop it, means nothing but trouble in the future.

Part 2—Design for Hope

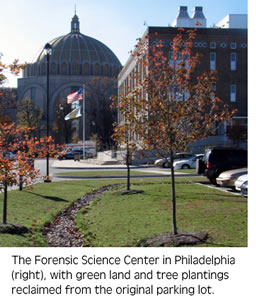

For years, the forensics laboratory in Philadelphia was a cramped space in the basement of police headquarters. Now it is located in an award-winning green building that may point toward a future for the abandoned shopping mall and its acres of parking.

For years, the forensics laboratory in Philadelphia was a cramped space in the basement of police headquarters. Now it is located in an award-winning green building that may point toward a future for the abandoned shopping mall and its acres of parking.

The Forensics Science Center began as an abandoned public school building—a solid 1929 structure surrounded by a large parking lot. The building had "good bones," in the words of the lead architect on the project. (A complete list of project participants is available on the American Institute of Architects web site.) The completed building provides a cheerful working environment, uses natural light and climate control in very creative ways, and manages the problem of chemical waste—which is both severe and inevitable in a forensics laboratory—with minimum damage to the environment. It also reclaims much of the parking lot for natural water runoff.

Traditional parking lots, which are impermeable, interfere with normal water runoff. The old school building parking lot posed a particular challenge because it is close to the Delaware River and had been a major source of water pollution in the neighborhood. Despite the need for parking for police vehicles, the architects managed to cut runoff substantially:

The previously impervious site now includes large areas of vegetated swales and buffer vegetation, improving water catchment by roughly 33%, while still meeting the Center’s demanding parking and servicing requirements. Linear vegetated swales paralleling the parking rows filter stormwater and allow it to evaporate or infiltrate the ground before it enters storm drains. Site plantings are drought-resistant, requiring less watering and maintenance than conventional landscaping. (From the AIA web site.)

Most parking lots are soul-destroying wastelands. The Forensic Science Building's parking lot, with its swaths of green and well-designed plantings, is not.

We can draw a number of lessons from the Forensic Science Building and its parking lot.

- Many buildings, even long-abandoned ones, can be rehabilitated with smaller carbon footprints. The initial cost is high, but as green rehabilitation becomes standard, it will drop. And by using less fuel, projects like the Forensic Science Building eventually pay for themselves.

- Parking lots can be less destructive if carefully planned. More important, they can be smaller, and the building less dependent on the private car, if we also learn another lesson of the Forensic Science project:

- Any green rehabilitation must include good connections to mass transit. Most of the employees at the Forensic Science Building take public transit to work because existing connections to the neighborhood were good. At any time, the majority of the vehicles in the parking lot are police cars and vans transporting evidence, not private cars used by the employees.

- Well-designed green buildings are pleasant places to work. The combination of large windows (for natural light) and airy rooms makes forensic work, which is often very distressing, easier to bear. Sickness and absenteeism dropped sharply after the laboratory moved to its new quarters.

The Forensic Science project and other green rehabilitation projects provide hope for the future of the dead space that is everywhere in our suburbs and increasingly in our cities. Much of it can be rescued. The question is whether it will be.

Part 3—Principles of Land Use Planning

In the 1950s, at the start of the large-scale migration to the suburbs, few thought of problems like the environment and water runoff. Now they have become crucial, both for the present and for the future. How should we plan and build for the future? And how can we reclaim the acres of dead space that surround us?

In the 1950s, at the start of the large-scale migration to the suburbs, few thought of problems like the environment and water runoff. Now they have become crucial, both for the present and for the future. How should we plan and build for the future? And how can we reclaim the acres of dead space that surround us?

Planning for the future is easier to envision. We have to change, and in at least these specific ways:

- We need to end the practice of building single stores or malls in the center of large surface parking lots. The era of the standalone shopping mall or big box store is coming to an end, whether we like it or not. In a world with limited space and resources, acres of surface parking—one of the characteristics of standalone shopping—will no longer be possible. Nor will they be desirable.

- We need to connect shopping, work, and living space. Stores and work within walking distance or an easy transit ride of where people live were once the norm. Suburban-style shopping is a historical aberration, brought on by zoning codes that separate living from shopping and working, and by our reliance on cheap fossil fuels. Fossil fuels are no longer cheap, either for consumers or for the environment. And the drive from home to school to store to work to mall and back and around has become increasingly burdensome as traffic has increased. The old-style zoning codes have failed. They need to change so that we can once again walk to work and to the shops.

- We need to revise building codes to require new homes, stores, and offices to be as sustainable as possible. In the long run, green buildings are cheaper to operate than traditional ones, and they are often more pleasant places to live and work.

- Planners and the community—not developers alone—must take responsibility for what happens to a neighborhood in the long term. If a mall or housing tract project fails now, responsibility for converting the land to new uses rests with those who own the land. Failure to reuse the land, however, has consequences for the whole community. Ownership of land may be private, but the fate of the land is a legitimate public concern that planners and the community (which should be part of the planning process) must consider when approving development projects.

- We need to start building in ways that deliberately allow for the needs of wildlife, and that allow more wild species to continue on the land. Preserving wild (or nearly wild) space is vital both for the environment and for the spirit. (Thanks to Marshall Massey for his suggestion in a comment.)

Following these four principles will not end problems with land use, but taken together they provide a more creative approach than the kind of development we now see in our suburbs.

As to the future of our current dead spaces, green rehabilitations like the Forensic Science Center in Philadelphia give some guidance. Sadly, many shopping malls and big box stores are not very good buildings and may not be salvageable. Nearly all of them, however, are located on tracts of land that would provide good mixed-use development. The shopping mall and the big box store provide an abundance of products; mixed-use development can provide an abundance of life. In the long run, we must move away from the mall and the big box and back toward communities and real neighborhoods.